TENERIFE :

THE MOUNT TEIDE NATIONAL PARK

INTRODUCTION

Tenerife is the largest of the Canary Islands, the Spanish archipelago of volcanic islands which lies in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of North Africa. But even though it is the largest of all the islands, it still measures no more than 100 kilometres (60 miles) along the greatest axis (NE-SW), with a total surface area of just 2,034 sq km (785 sq mls). The island is famous today as a hugely popular tourist destination, due to its equable sub-tropical climate and its sandy beaches which attract European visitors in their millions every year. But it has one other important claim to fame - a 3,718 m (12,198 ft) volcano which rises in its centre - the third tallest volcano in the world, and the highest point on Spanish terrirtory. El Pico del Teide is the Spanish name of this mountain, and Mount Teide is the English name. And today, Mount Teide is the focal point of a scenically very beautiful national park.

This web page is a photographic guide for those tourists who wish to visit the park, covering the routes into the park, what can be seen and how to make the most out of a visit. It also includes an account of how this park - and indeed the entire island - came into being. An appreciation of that increases the appreciation of everything one can see in the Mount Teide National Park.

The great volcanic cone of Mount Teide rises beyond a lava field and a sparse growth of Canary Island Pines

All photos were taken by the author during visits to Teide on 2nd and 5th of March 2014.

The Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean, and the location of Mount Teide

THE ANCIENT HISTORY OF TENERIFE AND MOUNT TEIDE

Tenerife, like all of the islands of the Canary archipelago, has a violent origin. All were born out of a series of submarine volcanic events over many millions of years, and Tenerife itself first rose above the surface of the Atlantic Ocean about 10 million years ago.

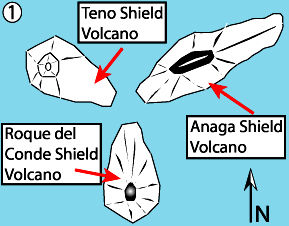

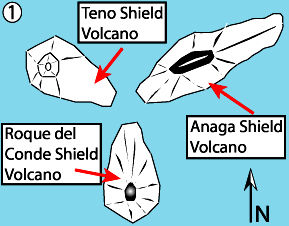

In its early days there were three small volcanic islands here - Anaga in the northeast, Teno in the west, and Roque del Conde in the south. But over a period of several million years, new eruptions and a gradual accretion of many layers of volcanic debris led to a coalescence of these three islands into a single land mass - the present day Tenerife - about 3 million years ago. A new volcano, Las Cañadas, grew in the very centre of the new island, and over time Las Cañadas developed into a massive cone, 4,500 m (14,800 ft) high and covering an area of up to 40 km (25 miles) in diameter. A relatively quiescent spell of primarily erosive processes followed, and this may have lasted as long as 2-3 million years, before volcanic activity escalated once again in the northeastern region of Anaga, and most notably in the centre of the island around Las Cañadas.

What happened next is unclear but at some time during the last 500,000 years, the summit of Las Cañadas dramatically collapsed to form a 16 km × 9 km (10 mile × 6 mile) caldera. Various theories exist; it may be that the volcano collapsed vertically as magma chambers below ground underwent a series of violent eruptions. However, the more favoured scenario is that Las Cañadas suffered a massive gravitationally-induced landslide to the west - a theory which may explain why the present day caldera escarpment rim only embraces the eastern half of the caldera. After this, several new volcanoes are believed to have developed in and around the Las Cañadas Caldera, only to collapse again. Then in the last 160,000 years, more cones thrust into the sky, and two of these on the western edge of the caldera were to become great mountains in their own right. One was Pico Viejo, the second highest volcano in the Canaries, with a summit at 3,135 m (10,285 ft). The other is Mount Teide. The emergence of these two volcanoes marked the final major stage to date in the development of the island.

The Main Stages In The Evolution Of Tenerife And Mount Teide

Originally three island volcanoes existed in this region of the Atlantic Ocean

Gradual accretion and coalescence of matter during multiple eruptions over time creates a single island

The development of two new cones within the caldera - Pico Vieja and Mt Teide - the mountains which exist toda

Originally three island volcanoes existed in this region of the Atlantic Ocean

Captions for this slide presentation may not be available on all smartphone formats, though the sequence of events is also described in the text

It seems therefore that the general form of the region was established by perhaps 100,000 years ago. Las Cañadas Caldera - one of the greatest collapsed craters in the world - remains as a lava strewn plain about 2,000 m (6,500 ft) above sea level. An escarpment which marks the eastern rim of the caldera rises in steep cliffs hundreds of metres high. On the western side the volcanoes of Mount Teide and Pico Viejo dominate the landscape.

But the emergence of Teide was not, of course, the absolute end of the story. The Island of Tenerife has never strayed far from the hot spot which first created it and the cones and vents of the volcanoes have remained active through to the present day, as we shall see in the next section.

The caldera looking north - On the left is Montana Blanca, the White Mountain, which lies northeast of Teide. On the right are the jagged boulders of Los Roques de Garcia

VOLCANIC ACTIVITY IN HUMAN HISTORY

Volcanic activity has been recorded on this island on numerous occasions during human history and since the first colonisation of the island by people known as the Guanches about 200 BC. Montaña Blanca, the 'White Mountain' north of Teide, erupted around 2,000 years ago. And Teide itself erupted little more than 1,000 years ago, producing the 'black lavas' which cover much of the slopes of the volcano today. That was the last eruption to date from the summit of Teide, but other vents have been busy. Indeed in 1492, Christopher Columbus reported seeing 'a great fire in the Orotava Valley' whilst passing Tenerife on his historic voyage to the New World. (In fact geological evidence suggests that this eruption occurred not in the aforementioned Orotava Valley, but rather at Boca Cangrejo in the region of the Santiago del Teide Rift to the west of Teide). In 1704-1705, eruptions commenced again at several volcanic vents on the northern Cordillera Rift at Volcán de Siete Fuentes, Volcán de Fasnia, and at Montaña de Arafo, and in 1706 in Santiago del Teide at Volcán de Arenas Negras. These were 'fissure eruptions' - eruptions of lava which derive not from a central cone but from a linear fracture in the Earth's crust.

The most recent upheaval within the caldera itself was in 1798 at Chahorra, a vent on the flanks of Pico Viejo, an eruption which continued over three full months. Then in 1909, a volcano called El Chinyero on the Santiago Rift produced the last violent display to date on the island. Seismic activity continues, and volcanic gases are still being emitted from Teide and from other vents, and there will probably be large scale eruptions again one day, though none are expected in the foreseeable future.

Two further events of note must be recorded before we leave this short discourse on the history of Teide, though these were not events of violent vulcanicity. Far from it; they were events reflecting the tranquility, beauty and merit of the region. On 22nd January 1954, 18,900 hectares (73 sq miles) of the Las Cañadas Caldera and the surrounding area were declared a National Park. Then on 28th June 2007, the Mount Teide National Park was created a Unesco World Heritage Site. Today Mount Teide is one of the ten most visited National Parks in the world.

The landscape surrounding El Chinyero - site of the most recent eruption in 1909

El Chinyero - the Teide National Park remains an active volcanic zone

VISITING THE NATIONAL PARK

To get to Mount Teide, there are bus services and tourist excursions. Bus services are run by the island-wide Titsa Company, and the National Park is served by the northern 348 bus line from Puerto de la Cruz, and the 342 line from the south. Most tourist hotels also offer coach excursions to Teide.

However, car hire is easy in Tenerife, and finding one's own way around the countryside is also quite easy. Hiring a car will give the freedom to explore the Mount Teide National Park in one's own time, stopping wherever one wishes. The road through the Las Cañadas Caldera is TF-21, which crosses the park in a south-west to north-east direction. Other roads provide links from across Tenerife, including TF-5 and TF24 from the northeast, TF-38 from the western side of the island, and - perhaps most importantly - TF-51 which serves the southern tourist resorts of Playa de las Americas and Los Cristianos.

Whichever road is taken, the rapid rise in altitude over quite a short distance ensures an interesting, meandering route and a rapidly changing scenic view as one climbs through any low cloud cover and ultimately through the tree line. There are no admission fees or barriers or any other restrictions to entering this park; the only awareness of the fact that you have arrived is in a signpost on the roadside. There’s no obvious transition in the landscape or in the flora either, though generally the park boundaries embrace the more barren, high altitude regions above the tree line.

Conifers growing sparsely as one approaches the tree line

VIEWING MOUNT TEIDE AND THE LAS CANADAS CALDERA - THE MAIN ATTRACTIONS OF THE PARK

Most of the natural features of the Las Cañadas Caldera are highlighted in red. All are illustrated in the photos.

However one enters the Mount Teide National Park one has to drive on TF-21 to get close to the mountain itself. If you are coming from the south of the island as I did, then on the right side, the well maintained road skirts the foothills of an impressive escarpment including the third highest mountain on the island, Mount Guajara. Here, the internal walls of the escarpment rise as great cliffs from about 2,100m above sea level up to 2,700m (6,900 to 8,900 ft). But most eyes will not be on the escarpment on the right; they will be looking to the left side where a great rugged plain exists, in places quite flat and populated by scrubby vegetation, but elsewhere strewn with jagged edged lava boulders - the legacy of past volcanic eruptions. This is the Las Cañadas Caldera. But there is no doubt as to what really takes the eye here. Beyond the laval plain rise two impressive volcanoes. First there is Pico Vieja, the second highest mountain on Tenerife, and then there is the cone of Mount Teide itself.

Driving along TF-21 (again from the south), one eventually arrives at a leftward bend in the road, which mirrors the curve of the caldera escarpment. One is now heading directly towards Mount Teide, and two features stand out on the approach. First there is a remarkable gravelly area on the side of one of the hills, very distinctive for its beautiful aquamarine colour, the result of a rich mineral deposit. This is Los Azulejos, a rock formation created by hydrothermal processes.

Then a little further on, on the left side of the road is a region of giant, jagged outcrops and standing stones known as Los Roques de García. The final one of these standing stones is called Roque Cinchado, and the sight of this monumental stone with Teide in the background is the most iconic of all views of the volcano. There is ample parking near to Los Roques, and on the other side of the road, there are more parking spaces to serve the only large tourist building in the National Park, the Cañadas del Teide Parador, a small hotel and restaurant where guests can have lunch with great panoramic views of Mount Teide, Montana Blanca (the White Mountain) to the north, and Las Cañadas Caldera to the south. The Parador also includes a small Visitor's Centre. (Another Visitor's Centre can be found further north on TF-21 at El Portillo).

In many parts of the caldera there are pathways which can be walked, but one must adhere to these designated routes to avoid any damage to delicate rock formations or rare plants. There are also guided tours available, which must be booked in advance. From Los Roques and the Parador, it is but a short drive further along TF-21 for the turn-off to a cable car station - the only way for most tourists to get closer to the summit of Mount Teide, and this will be the feature of the next section.

The lonesome pine - As one travels along Route TF-21 from the south, trees become sparser with greater altitude

Photo opportunities abound on the winding roads up to the National Park. The road is in the lower part of the picture

The Three Highest Peaks

Mount Guajara - the third tallest mountain on Tenerife - stands high at 2,718m

Pico Viejo - the second tallest mountain on Tenerife at 3,135 m. The slopes on the left flank of the volcano feature laval flows from the 1798 eruption

The eastern face of Mount Teide - the tallest mountain on Tenerife at 3,718 m

Los Azulejos, a distinctive greenish outcrop on the Las Canadas escarpment

The cable car to within 200 m of the summit of Mount Teide, and the Las Canadas escarpment in the background

THE CABLE CAR

The route to the restaurant and Los Roques de Garcia is easy by road, but if one wants to get very much closer to the summit, then one must soon leave the car. There are hiking routes to the top, but these are not for most tourists, as they involve a grueling 4-5 hour climb, and at this altitude the rarefied atmosphere means that one must be properly prepared. The way for most to ascend the mountain is by cable car. First proposed in 1929, it was 1962 when construction of the cable car system finally got underway under the directorship of the company Teleférico del Pico del Teide S.A. It took 8 years to complete, but on 2nd August 1971, the cars began operation. Renovations of the cars, the stations and the towers since then have kept this system at the forefront of design. The route consists of just two stations - a base station at 2,356m and an upper station at 3,555m - and two cars, one on each rail.

There are plenty of parking spaces along the road and then in a car park at the lower station, where facilities such as a shop, a self-service restaurant and toilets, and of course a ticket office, are to be found.

The most famous 'picture postcard' image of Mount Teide features the standing stone of Roque Cinchado in the foreground

The countryside by the lower cable car station, at the foot of Montana Blanca. The dark band is lava from Teide's most recent eruption 1,000 years ago

The scenery close to the lower cable car station. Topo de la Grieta is the peak in the background. Note the lava flow on the left - reddish due to oxidation processes

THE UPPER STATION

The cable car journey to the upper station takes about 8 minutes. Here there are less facilities, but this may be deliberate because viewing space is limited, and the more time each person spends here, the smaller the number of people who can go to the upper station during the course of a day. Also it can be decidedly chilly at this altitude. Most visitors therefore do not spend a huge amount of time here. Nonetheless, the cable car ride is certainly well worth while because from the viewing platforms here, a panoramic view is possible of the whole of the Las Cañadas Caldera and escarpment, and to the north a long mountain range known as the Cordillera Dorsal (also known as the Dorsal of Pedro Gil).

The Cordillera Dorsal mountain range has previously been mentioned as the location of fissure eruptions on Tenerife in 1704-1705. It is a 25 km (15 ml) long mountain range with an average height of 1,600 m (5,000 ft) and a highest peak of 2,350m (7,800 ft). The range has been built up through repeated outpourings of lava over a period of about one million years.

Most who arrive at the Upper Station will return down the mountain by cable car soon after. But there are other options. There is the possibility of trekking to two other vantage points. These are La Fortaleza and Pico Viejo, which offer further views of Northern Tenerife and the crater of Pico Viejo respectively. And there is also the possibility of climbing to the very summit of Teide - just 163 m (530 ft) above the upper cable car station. These routes will be covered in the next section.

The view to the southeast from the upper station. The escarpment marks the perimeter of the Las Canadas Caldera

The view northeast from the upper station. Note the red lava flows in the foreground and the dark lava flow in the centre, the low cloud bank, and the 'Cordillera' Mountain Range in the distance

2,602 m (8,536 ft) high Topo de la Grieta and lava from Montana Blanca

THE SUMMIT AND OTHER HIGH VANTAGE POINTS

The route to La Fortaleza Vantage Point heads northeast, offering views of Mt Teide's cone, Montaña Blanca, and the black lava flow from Teide's most recent eruption. Most of the northern aspect of Tenerife is visible from here, including La Orotava Valley and the Cordillera Dorsal Rift that leads northeast to join with the Anaga Massif. The path is flat.

The path to Pico Viejo Vantage Point offers the chance to look into the crater of the second highest volcano on Tenerife. 800 m in diameter and 3,104 m above sea level. This route also takes in views of the lava flows of 1798, and the Las Cañadas Caldera, Mount Guajara, the southern coast of Tenerife and the Island of La Gomera.

One other option - the route to the summit itself - has obvious attractions. The first known ascent of Mount Teide was by an English party c 1650, but today, the Telesforo Bravo Route - a turning on the La Fortaleza pathway - allows anyone of sufficient fitness and good health to climb the last 163 m to the top to take a look into the crater of Mount Teide itself, and a panoramic view of the whole island (though low oxygen and sulphurous fumes can make breathing difficult and progress slow).

Both the La Fortaleza and Pico Viejo paths can be walked without permits, but the route to the summit requires a free permit which must be applied for in advance. The reason for this is because numbers have to be limited. (Sadly, on my visit none of these routes were open as ice on the paths had made conditions hazardous).

The view of the summit from the upper cable car station - the closest a visitor can get without walking and without a permit

Mount Guajara and the Las Canadas escarpment. In the foreground are the remains of a former crater of Mount teide, upon which the present cone developed

THE WESTERN LANDSCAPE OF THE TEIDE NATIONAL PARK

Many will approach the volcano from the south or the north on TF-21 and arrive at the Parador, and from there head on up to the cable car, before returning home by the same route. By doing so, they will have seen almost all of the sights so far described in the text. But they will also have seen Teide from only one side, and that may be a pity, because depending on the time of the year the volcano may present its prettiest snow-capped face from another direction. From the west and southwest there is the best view of its almost perfect cone, as well as picturesque scenery including Pico Viejo and the Canary pine trees which grace the lava fields in this region of the park. In late winter when these photos were taken, snow had lingered longer on these slopes of Mount Teide, and made this the outstanding panoramic view to see.

Two sites are of particular interest on the lesser travelled route of TF-38 from the west. First there is El Chinyero, notable as the site of the very last eruption to date in the year 1909. Here one can walk through a lava field laid down little more than 100 years ago, and see Teide at its best (the final photo on this page).

The scenery of the Samara Volcano

A little closer to Teide is the Samara cinder cone, a small volcano formed out of a single eruption in comparatively recent times. The appeal of this site is the view of Teide and Pico Viejo (shown below), and the presence of several walking routes including a half hour walk to the Samara crater rim. All around on the ground one can see little black pyroclasts - debris emitted during the Samara eruption.

Of course if one has time, the answer is to travel all the roads around the volcano. That may not be a realistic option for those who want to fit theme parks and sunbathing into their itinerary, but nonetheless, the option is there for true volcano enthusiasts.

The western approach to the park along TF-38, and from left to right beyond the last of the Canary Island Pines, we see three very different volcanic structures - Mount Teide, Pico Viejo and the black cinder cone of Volcan de la Botiga

FLORA AND FAUNA

The route up to the National Park of course gains considerable altitude within a short distance, and is made all the more interesting by the changing vegetation encountered with altitude. Below 500 m, the vegetation is typical of dry sub-tropical landscapes in the Canaries with many succulents including Cacti and Euphorbias, but these give way to forests of trees as one ascends higher, including laurels, holly, myrtles and juniper among the predominant species. Ultimately however, just one species of tree produces the characteristic upper forest of the mountains - the Canary Island Pine (Pinus canariensis) is quite bountiful between 1,000 m and 2,000 m (3,300 to 6,600 ft). But the caldera of Las Cañadas is above 2,000 m and above the tree line, and here vegetation is much sparser. Soil which forms on the lava flows of the Mount Teide National Park is nutrient rich, but thin, and species which survive here have to be specially adapted to the high altitudes, bright sunlight, high temperature fluctuations and arid conditions, Consequently, a high proportion of Teide's species are endemic (unique) to the island, or even to the mountain park. Characteristic plants include Teide Bugloss (Echium wildpretii), the Canary Island Wallflower (Erysimum scoparium) and the Teide White Broom (Spartocytisus supranubius). One unique species, the Teide Violet (Viola cheiranthifolia) can even be found at the summit of the volcano which bears its name.

Prickly Pears (not native) and shrubby Euphorbias are typical of the lower mountains

Similarly, animal species are comparatively sparse, but several occur only in this region. At least 70 species of invertebrate are found only in the National Park and nowhere else on Earth. Only a few types of reptiles, birds and mammals are common on the mountain.

Succulents are well represented among the mountain rocks

PHOTO OPPORTUNITIES AND VISITOR INFORMATION

For those who regard a good photo record to be half the pleasure of a trip to a place of scenic interest, the Teide National Park doesn’t disappoint. Of course there are areas where the cliffs are steep and there are no spaces for pull-ins. There are also stretches of road through the lava fields where cutting parking spaces would not be appropriate aesthetically. Nonetheless there are plenty of places where one can pull off on to gravel roadsides, and a fair number of purpose built lay-bys, usually paved and attractively walled with natural-looking stone which is in keeping with the environment. These are all signalled in advance by a signpost with a picture of a camera, indicating a photo opportunity.

Visitor information is first rate. In most of the car parking areas there are descriptive panels, which will usually include an illustration of the field of view, with annotations giving the names of major features. The panels may also give a brief history of what we are looking at, to give an understanding of how the landscape came into being. All this information is usually given in three languages - Spanish, English and German.

A typical explanatory panel describing the sights and the geological history

One of the descriptive panels - this one tells of the eruption of Pico Viejo in 1798

Among the possible ways of getting to Teide are the comfort of a car or the strenuous exercise of a bicycle - I chose a car

DRIVING SAFELY IN THE PARK

There is a natural concern about the safety of driving along mountain roads, but on the approach to the Mount Teide National Park, this really shouldn't be something to worry greatly about. The roads are well maintained, well marked, and wherever a steep drop exists, metal crash barriers or concrete blocks are in place. There are areas without barriers, but these are areas in which the slope is gentle, or short, or broken by thickly planted trees. There is of course no street lighting, so ensure that any visit is completed before nightfall, unless astronomy or sunsets are your thing. (See under 'Recommendations')

Slightly more danger would be posed by falling rocks. In some areas there are warning signs, whilst in other particularly vulnerable stretches of road, netting is in place, and in a few select places a concrete roof over the road shields the cars from falling debris.

The biggest danger probably comes from the large numbers of cycling enthusiasts who ride through the park. One must be careful when rounding bends or overtaking.

Los Roques de García

RECOMMENDATIONS

Mt Teide dominates its surrounding landscape in a way which very few mountains can. Almost from anywhere on the island the snow-capped peak of this volcano is visible, and its near perfect cone cannot be mistaken for any other mountain.

Time of year and time of day brings different sights or experiences, though many advise that spring is the best time to visit when there may still be snow on the upper reaches of the volcano whilst the spring flowers bring extra colour to the landscape of the Las Cañadas Caldera. One is also likely to find a shorter queue waiting for the cable car lift, than would be the case in the height of summer.

It has already been suggested that it may not be advisable for tourists to travel the winding mountain roads after dark, but having said that, dawn and dusk can bring beautiful changes in colour tone on the rock faces, and of course in the sky above and around the mountain top. And for any amateur astronomers, the caldera after dark may be a dream location - clear skies unpolluted by street lighting can give wonderful viewing of the starry sky (there are astronomic observatories elsewhere in the park).

The truth is, whenever one visits, the Mount Teide National Park really is a must-see experience for anyone who comes to Tenerife. About three million visit the park every year, and that is no surprise; the dramatic landscapes of the caldera, the panoramic views from the upper reaches of the volcano, and the geological interest which permeates the entire region make this one of the most attractive and memorable of all the world's national parks.

A Final View - The western face of Teide, photographed from El Chinyero

I'd Love to Hear Your Comments. Thanks, Alun